When you look at Arsène Wenger what do you see? A shining light for longevity, the last of his kind overseeing a period of time at one club, something that is now unique? A 66-year-old manager who seems past it, his methods overtaken by younger, hungrier, craftier coaches? A stubborn man? A loyal man? A romantic? A revolutionary? A relic? A survivor?

It explains a lot about him, and how he is perceived, that after an extraordinary 20 years at Arsenal, he can be all of them. Here we chronicle the seven ages of his time at the club.

Brave New World (1996)

Nobody, least of all the man himself, envisaged the depth of the opportunity ahead when Wenger weighed up the prospect of joining Arsenal in 1996. He gave the offer careful thought in his apartment in Nagoya, where he was living while manager of Grampus Eight. His spell in Japan provided an experience that fascinated him. Far away from the madding crowd of European football, he immersed himself in a culture and in a way of life that was by its nature challenging, engaging, eye-opening, and at times lonely. The work was stimulating. But friends, family and familiarity were almost 10,000km away.

The Arsenal opening represented a mighty leap in every way – professionally, culturally, personally. “I was at a dangerous point and I had to make a decision. I felt that if I didn’t come back now I would stay forever in Japan,” he explained. “After two years you get slowly emerged into this spirit. What you miss in Europe is slowly drifting away. I was at a point where I thought, I will make my life here if I don’t come back now.” His wife was pregnant with their daughter.

Either they would make the big move to Japan to join him and Wenger would commit to deepening his roots in Asia, or he would return to Europe. In hindsight, this was a sliding doors moment. Who knows how his subsequent decades – and Arsenal’s – would have turned out had he taken the other decision?

Half a world away in London, his friend, the then Arsenal vice-chairman David Dein, awaited Wenger’s choice. From their first chance meeting in 1989, when Wenger was passing through London with some time to kill on the day of a north London derby, Dein had been wowed by this individual who struck him as completely different to the average manager. He first proposed the idea of appointing this clever, worldly Frenchman working in the J-League in 1995, only for his fellow board members to reject it as far too risky. A foreign manager? What an audacious suggestion. There was no evidence to suggest it would work at all.

There had been only one experiment with a manager from abroad in the top flight before. Aston Villa hired Dr Josef Venglos (predictably welcomed as “Dr Who?”) in 1990. He arrived fresh from coaching Czechoslovakia at the World Cup, a multi-linguist who could communicate in Russian, Portuguese, Spanish and English as well as his native tongue.

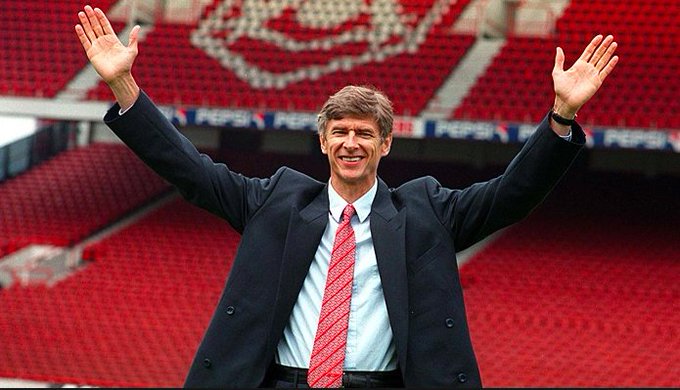

22 September 1996. When Wenger made his first public appearance as Arsenal’s new manager, sporting a gaudy club tie and dark blazer, with a press conference at Highbury to formally introduce himself before properly starting work on 1 October, nobody knew quite what to expect.

The only other foreign coach working in England had only just been promoted – Ruud Gullit took over from Glenn Hoddle to become Chelsea’s player-manager during the summer. After “Dr Who?” came “Arsène Who?” Unlike Gullit, who had a global reputation and was already a familiar face in Premier League football when he was appointed to the Stamford Bridge dugout, Wenger was a virtual unknown.

Pass With Flying Colours (1996-1998)

It was Patrick Vieira who started the ball rolling. This rangy and athletic young midfielder – another Frenchman few in England knew anything about – was signed all of a sudden from Milan and represented a sort of advanced party before Wenger was freed from his commitments in Japan to start work with Arsenal. Actually it was more of an advanced present.

Vieira made his debut midway through the first half of a modest performance against Sheffield Wednesday at Highbury under the caretaker control of Pat Rice. He came on and it was a shining lightbulb moment. Dennis Bergkamp, who was injured and watching from the sidelines, felt the crackling energy sweeping through dear old Highbury. “When he came on he changed the game. He completely changed the game!” the Dutchman recalls. “And I think everyone in the stadium was thinking, ‘What happened here? Did I really see it right?’”

For Bergkamp, the arrival of Wenger built a bridge between the football of his past, his education in the Dutch ideals of total football, and the never-say-die English football attitudes that were embodied by Arsenal’s steely back four. There was a kind of symbiosis. Consider how Bergkamp absorbed the toughness which helped him to electrify the Premier League, or how Adams had the freedom to burst on to a chipped pass from Steve Bould to score with an impeccable volley.

The Wonder Years (1998-2006)

Wenger’s first decade yielded convincing, regular success. It was not without its towering disappointments. In between the doubles of 1998 and 2002 were three frustrating seasons of being close but not winning. They were league runners-up each season behind domestic rivals Manchester United, and also lost a bunch of painful semi-finals and finals. The rivalry with Alex Ferguson’s team was intense and compelling.

But overall, during the period between 1996 and 2006, Arsenal won the Premier League three times, FA Cup four times, reached the Champions League final for the first time in their history and went through the 2003-04 league campaign undefeated. It was an era to bear comparison with the dominance masterminded by Herbert Chapman in the 1930s.

A decade of high achievement is what the subsequent Wenger years are inevitably measured against. Recall of that time is important not only for the substance but also the aesthetic style. A team that had Thierry Henry in his prime leading the charge, with the artistry espoused by Bergkamp, Robert Pirès, Freddie Ljungberg, Vieira, Kanu and company buzzing around the pitch (not to forget a toughened defence that took every goal conceded as an affront), won many admirers.

Wenger’s time at Arsenal has coincided with the globalisation of the game, and creating an imprint, an identity – one that was in opposition to the “Boring Arsenal” tag they had carried for years – is something he is quietly proud of. “Sometimes when I speak to foreign coaches and ask about a player and they say, ‘This is not an Arsenal player’ this is the biggest compliment you can get,” Wenger said.

The Great Survivor (2015-16)

Some supporters frustrated by the ratio between high ticket prices and club honours vent their spleen and hold up banners. Others feel a sense of loyalty and affection for a man who has given a lot of himself to the club during his tenure. Many are stuck in the middle.

There is also a range of emotions among ex-players, men who in some cases grew up while playing in one of Wenger’s teams, and experienced defining moments of their careers in that time. It is curious that Wenger prefers to keep a professional distance with some of the greats who are starting out in coaching – Vieira, Henry, Bergkamp are among those who would have loved to return to work at the club but for whatever reason the invitations have not quite worked out.

Whatever happens and whenever it happens to end this collaboration between manager and club, Wenger is the last of his kind. The average timespan for a manager in England’s professional game is currently 13 months. We will not see a 20-year boss at elite level again.